21st Century Filmmaker

Mike Mills may be a celebrated graphic designer and artist, but movies are where he’s found his storytelling home. Here the humble, multifaceted creative—and ideal Semi Permanent collaborator—opens up about his process, getting personal, and why he treats directing like running for President.

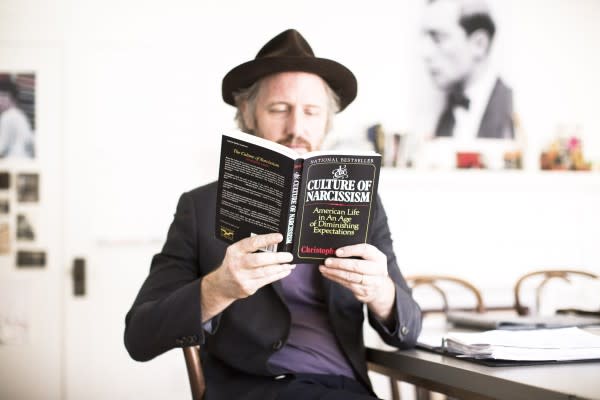

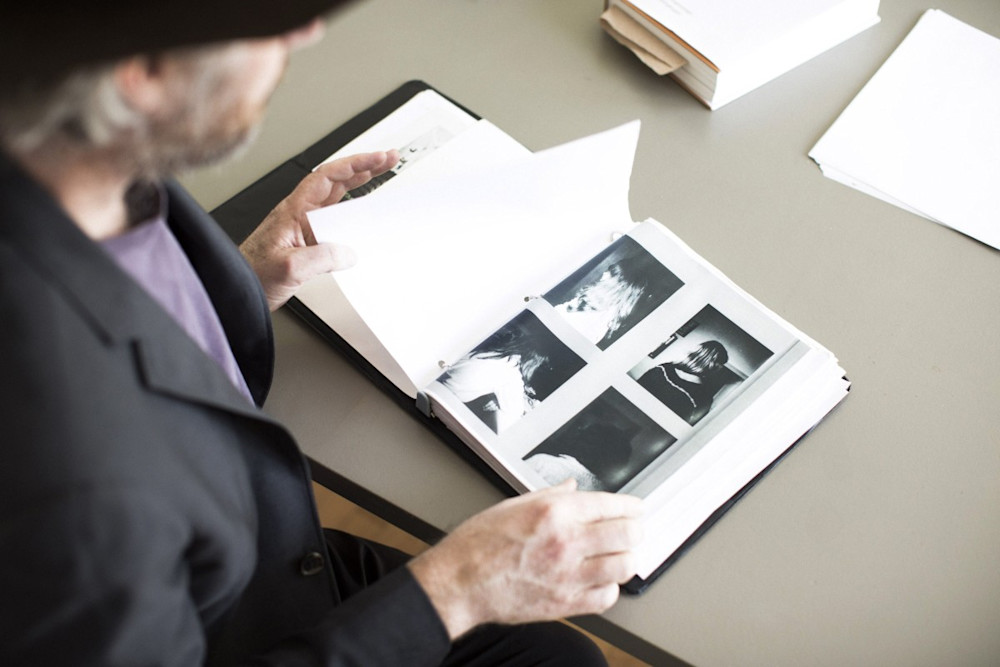

Mike Mills’s footsteps thud on the wood staircase as I follow him down to the lower level of his charming Los Angeles studio, descending from the main sun-drenched room into darkness. The window of this small editing room is covered in black fabric, in the corner sits a desk with a couple of flat screen monitors, and as my eyes adjust I realize I’m immersed in the makings of the 49-year-old auteur’s latest feature film, 20th Century Women. Two 4’ x 8’ black poster boards are checkered with rectangular images—stills from footage he shot in Santa Barbara and L.A. last fall of a story inspired by his own adolescence. A system that, Mills says, allows him to see the “forest” when he’s deep in the trees of editing. Beautifully articulated photos of the film’s stars—Annette Bening, Greta Gerwig, and Elle Fanning—surround me, fragments of a narrative that Mills is slowly, painstakingly sculpting and winnowing. In the dim space, quiet save for the subtle hum of technology in sleep-mode, I realize I’m not only looking at film stills, but also the tangible ephemera of Mills’s layered, inspired creative process, one that, when it comes to his filmmaking at least, is a many-yeared journey. “I’m good at marathon running. It’s definitely a marathon,” Mills says, when we sit down to chat at the large table that takes up most of the studio’s main room. “And I’m very good at delayed gratification, says my therapist.” These kinds of humorous, self-deprecating asides seem almost compulsive for the artist, graphic designer, and filmmaker, whose body of work spans nearly three decades and as many fields.

Mills got his start in the art world, “breaking plates” for the likes of Julian Schnabel. But after graduating from New York City’s Cooper Union, it was a world he wanted little to do with. “It was gross,” he says. “It’s the most corrupt, duplicitous, rarified-for-the-white-wealthy thing you could do.” So he turned to graphic design, to make art for the public sphere, and quickly made waves as part of group of artists, now often referred to as the Beautiful Losers, whose DIY ethos burgeoned in direct opposition to “the Mary Boone money scene” of ’90s fine art. He designed now-iconic album covers for Sonic Youth (1995’s Washing Machine) and Air (1998’s Moon Safari). He directed music videos for Moby, Yoko Ono, and Blonde Redhead. He helmed genre-shaking commercials for Gap (remember the Khaki dance videos of the late ’90s?). Miranda July’s short story collection and recent novel, last year’s The First Bad Man, are among the books he’s created covers for (July also happens to be his wife and the mother of their 4-year-old son, Hopper). But he’s likely best known for his filmmaking.

In 2005 he released Thumbsucker, a quirky, coming-of-age indie based on the Walter Kim novel starring Tilda Swinton, Keanu Reeves, and a teenage Lou Taylor Pucci as the thumbsucking lead. But it was his 2010 movie Beginners that really solidified his place in the world of film. It was also the perfect amalgamation of all of his creative endeavors. “Beginners kind of represents all the things I can do, they’re all in one bucket finally,” he says. It was a movie that resonated deeply with audiences and critics alike, perhaps because it was a narrative that originated so deeply within Mills himself. It tells the story of Oliver (played by Ewan McGregor), a Los Angeles-based graphic designer whose 75-year-old father comes out as gay in the wake of his wife’s (Oliver’s mother’s) death. Shortly thereafter he’s diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. It was inspired by Mills’s own life. “My dad was dying and he told me a story. He said, your mom hid her jewishness and I hid my gayness and we joined America and we got married,” Mills says. “And I was like, I’m making a movie about that.” The movie is infused with an authenticity that burrows straight to the heart. It’s a smart and poignant meditation on love and death and family with as many funny moments as there are touching ones. It garnered Christopher Plummer, who plays Hal, Oliver’s dad, both a Golden Globe and an Academy Award. Mills received Independent Spirit nominations for Best Director and Best Screenplay, and for good reason: it was the movie that helped him find his voice. “It’s like this intersection between things that are very personal, memory-based, and how that intersects with much larger historical societal issues,” he says. “Wherever you are you can always do a Z-axis and look at it from 10,000 feet like, Ok, the personal is political or I’m a subject in history or I’m on this particular piece of land, how does that relate to everything else? That sort of prism-ing, or kaleidoscoping, I feel like that’s something I’m endlessly doing and is endlessly rich for me.”

“I’m good at marathon running. It's definitely a marathon... and I'm very good at delayed gratification, says my therapist."

Mike Mills

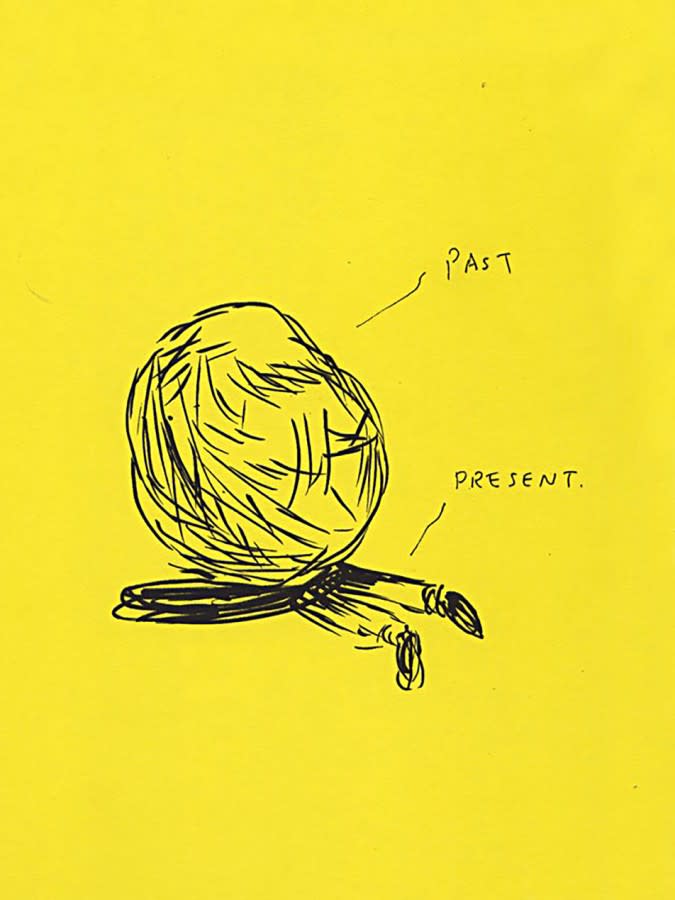

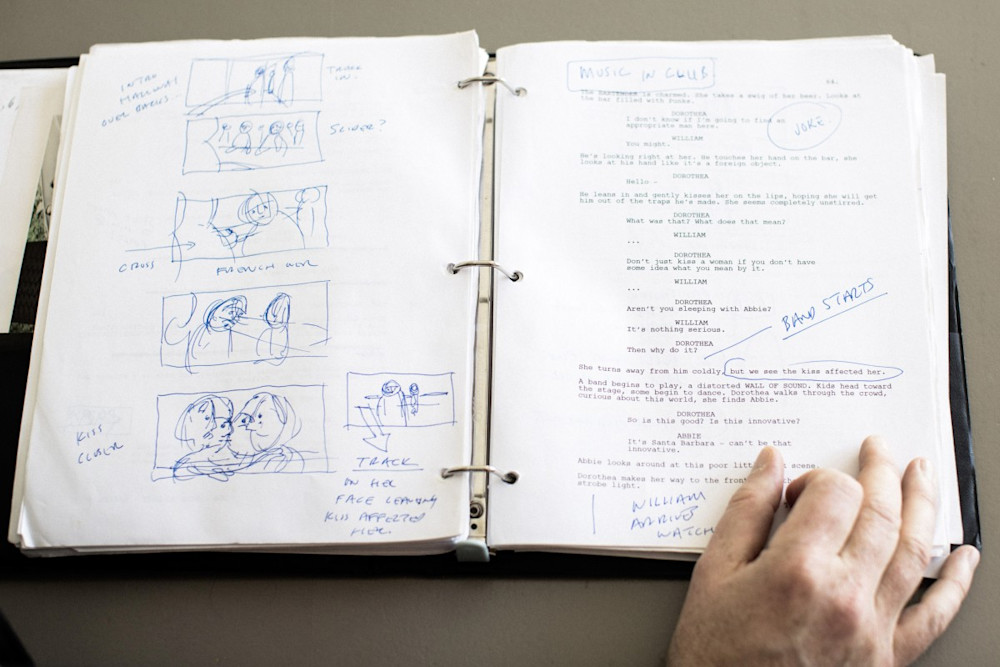

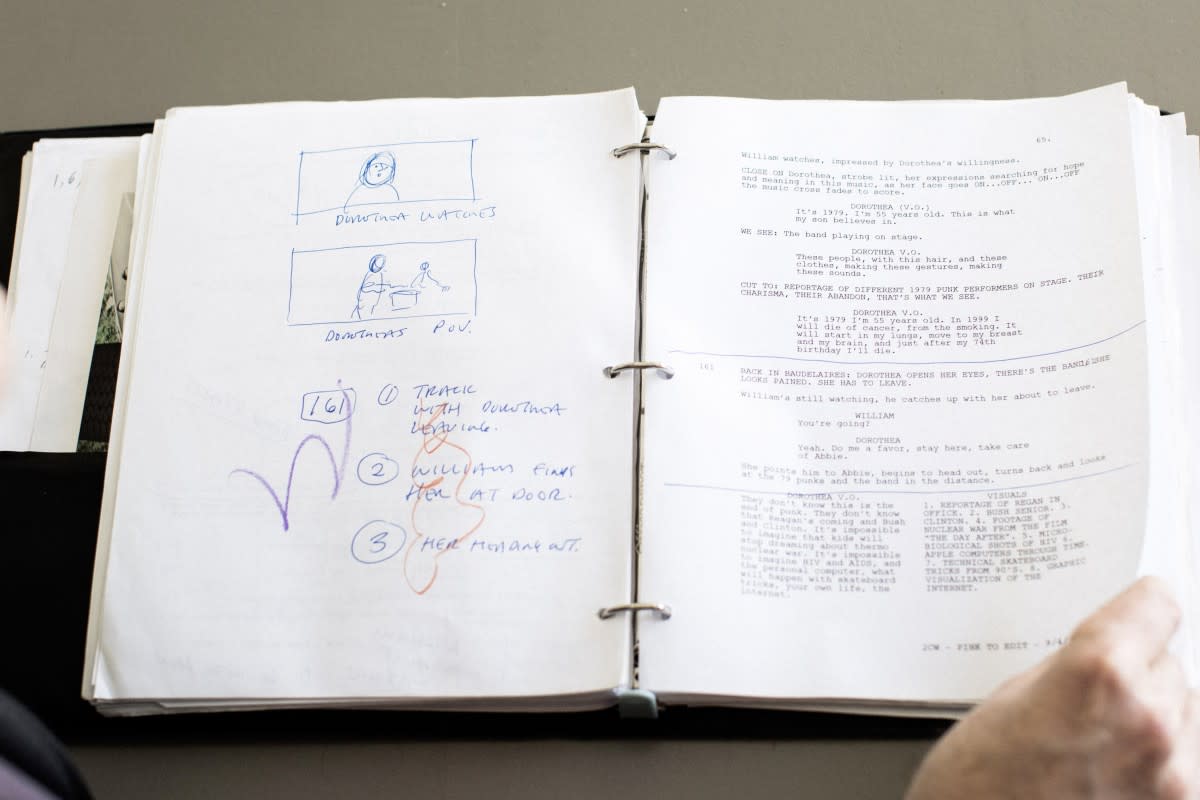

All that kaleidoscoping starts in a decidedly simple way: with index cards. That’s what Mills uses to jot down memories or bits of dialog or sometimes just a simple word when embarking on a film project. For Beginners, he wrote magic on a card because he wanted to inject the movie with a bit of the unknown. That card worked its way into the film as Arthur, Oliver’s “talking” dog. After many months and the creation of several shoeboxes’ worth of cards, a storyline starts to emerge. For Mills, this is when things get difficult. “I’m really horrible at plot,” he says, tipping up the brim of his fedora, rubbing his forehead, and pushing it down again. “It just feels like lying and I hate it. Ultimately it’s necessary but it’s just totally unnatural to me.” After index cards come notebooks, which Mills uses to formulate an outline from lists and clumps of info he hopes to weave together. He grabs one of the 20th Century Women notebooks sitting near us on the table, puts his glasses on, and begins flipping through scribbled-on pages. “[The movie’s] set in 1979, it was a really interesting year,” he says, before pointing and reading aloud from a list jotted on the page. “Apple computers went public. The first test tube baby. High-fructose corn syrup. The Iranian revolution. The end of men,” he says with a laugh.

But if writing is, as Mills puts it, “very specific and hard and weird,” directing is the part of the cycle when he’s forced to overcome his self-proclaimed shyness and reclusiveness, an element he’s completely embraced…literally. “I hug a lot, I kiss a lot, I’m the most encouraging, exuberant version of myself. ’Cause you’re the captain of the ship, and there’s like 60 people following you around. At first that was really scary and now I’ve grown to fully love that,” Mills says about being on set, where he completes his transformation by wearing a suit every day (“there’s nothing worse than like a retired skateboarder look,” he says, though his purple T-shirt, black jeans, and white sneakers are casually stylish). “It sounds very grandiose but it’s like, this is as close as I’m going to get to running for President, and I kind of treat it that way.”

I realize even his studio is an example of the Z-axis idea that informs so much of his work. The small duplex has a slatted wood fence and a bright red door, placing it firmly in the aesthetic of L.A.’s current gentrification, but it was built in 1925, when Hollywood was in its gestational stage, on its way to becoming the world’s biggest entertainment juggernaut. On one wall hangs a black and white poster of Louise Brooks; above the mantle is one of Buster Keaton, both silent film stars who also worked in and around this Silver Lake neighborhood. As he talks Mills leans back in his chair, emphasizes his points by tapping his hands on the table, and is constantly moving his fingers across its smooth surface. He has a thoughtful manner of speaking, peppered with the “likes” of a true Californian, and considers my questions before answering each one with a humility I didn’t anticipate. His kind blue eyes crinkle when he laughs, which is often at his own expense. And our conversation has some of the same emotional characteristics of his films—it feels familiar, and, strangely, safe. “I’m sort of annoyingly sincere and heartfelt,” he says. “On a very deep level I feel alone, not in sync. So I make work to get in sync—for me as a director to connect to people, and for my characters to connect to something. And that’s behind everything.”

“I’m really horrible at plot... it just feels like lying and I hate it. Ultimately it’s necessary but it’s just totally unnatural to me."

Mike Mills

Though he swears his deep knowledge of film is more a result of years of accumulation rather than rabid consumption (“I’m like a Criterion Collection whore”), the names of directors and cinematographers and movies crop up repeatedly, no matter what aspect of the creative process we’re talking about. When it comes to influence and admiration, Fellini is toward the top of his list, and seeing Jim Jarmusch around his East Village neighborhood when Mills was living in New York is one of the things that made filmmaking seem more accessible, when the idea of Hollywood felt too big and “over there.” He also praises István Szabó, the Hungarian director behind the 1970 autobiographical movie Lovefilm, French New Wave director Jean-Luc Godard, and, not surprisingly, Hal Ashby, whose work is infused with a similar sincerity. “I don’t love this film as much as I used to, but Harold and Maude gave me, as an audience member, this tremendous feeling of openness. It created a space where it’s ok to be vulnerable,” he says. “I like that. And so in some ways I like trying to make that for people.”

Making that space, especially when the subject matter is so deeply personal has its drawbacks, but reliving trauma isn’t one of them. On the set of Beginners, and in the press whirlwind after its release, people often assumed the process of writing and filming his father’s illness and death was difficult or cathartic. “I was like, ‘Fuck no,’” he says, incredulously. “Living it is hard.” In fact, Mills jokingly suggests that everyone who’s experienced trauma should make a movie about it—the act of writing and rewriting it alone creates enough distance from the event to diffuse the intensity of emotion. Conflating art with real life isn’t a problem either, he says. “Christopher Plummer is so not my dad. And I didn’t ask him to be. I just asked him to live with the same issues that my dad lived with,” he says. “And Annette Bening’s not my mom. So in that way it’s very clear.” But that doesn’t mean there isn’t some funny overlap. One day, Mills was telling another parent at his son’s preschool about his dad’s coming out and his subsequent death. She suggested he watch a wonderful movie, the one with Christopher Plummer. And the crossover is sometimes rooted more in aesthetics than emotion. “The sweater that Ewan wore in the [Beginners] posters is actually my sweater, and I like to wear it, it’s still one of my favorite sweaters,” Mills says. “But once in awhile, like, when I go to [Silver Lake eatery] Forage the guy behind the counter says, ‘Hey, isn’t that the sweater in your movie poster?’ And I’m like, fuuuck.”

“I’m sort of annoyingly sincere and heartfelt. On a very deep level I feel alone, not in sync. So I make work to get in sync—for me as a director to connect to people, and for my characters to connect to something. And that’s behind everything.”

Mike Mills

When it came to shooting 20th Century Women, he actually welcomed the chance to revisit his adolescence, and commune with the spirit of his mother who, he says, was a bit too thorny for that when she was alive. It was an experience he describes as “honeyed.” Of course he chides himself about the gentleness of his work, but he wouldn’t have it any other way. “I can often find my way to be bullshit. Sometimes I’m like, ‘Oh god, Mike, can you just stop being sweet and all that?’” he says with a laugh. “Which is hard, I guess. But on the other side…I watched Mad Max: Fury Road on the airplane. Everybody loves that movie and I was like, ok, in a world where people die, where horrible things happen, all sorts of pain, why spend all this energy and money and creativity making hell? I really can’t make hell, I will get so depressed. So I have to make something that reminds me of the light."

Photography by one of our favourite people, Mike Piscitelli, a charming man who shares very similar traits to Ewan McGregor's best friend in Beginners - coincidence?