In Conversation: Anna Diaz, Hamill Industries

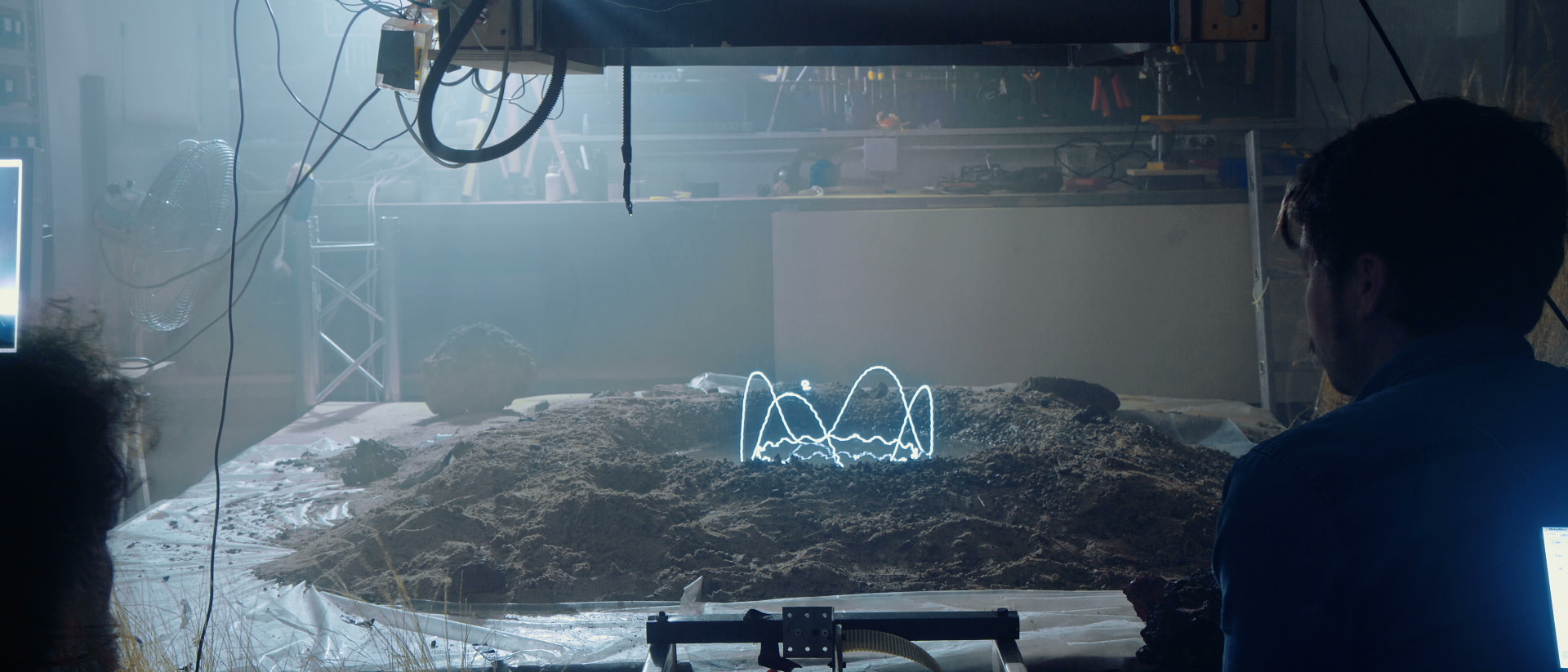

Hamill Industries is a creative studio partnership composed of directors, inventors and mixed-media artists Pablo Barquin and Anna Diaz. Their body of work focuses on marrying computerised, robotic and video techniques to explore concepts from nature, the cosmos and the laws of physics.

Hey Anna! I know it’s late over in Barcelona. Thanks so much for staying up to talk.

Oh no problem, we're usually up late tinkering on projects anyway.

Let's start with a really important question: what role does Tinta [your dog] play in the studio?

Hahaha, she's the one that keeps the team together. Pablo and I are partners, this is a family based studio and we're very proud of that. Everyone always says 'don't work with your partner' but we manage it and since we don't have children, Tinta is the one who often brings us back to reality. She's always like 'I need to go for a walk' 'I need to go to the park' 'wake up', otherwise we would be at the studio all the time. She's the glue that keeps us grounded.

The studio is described as ‘research-driven storytelling’ and I’m curious about the principles of that mantra.

Even though we work with technology, inventions, materials and abstract ideas, we both come from a very traditional storytelling background. We always want to tell a story, even if it’s abstracted through technology or inventions or organic settings. With Floating Points, for example, we’re communicating the way he makes music and the textures in his compositions rather than just showcasing beautiful visual effects.

From our previous commercial roles, both of us realised that technology and CGI is often only used to create a ‘wow’ effect with no substance to it. So whether we’re working with digital or analog, there has to be a story rather than it just being something nice to look at.

The studio’s work now spans so many different forms and materials and constantly deviates from itself. Was that the intent from day one?

Hamill Industries was founded with the spirit of experimentation. Prior to this our workflow was all computer based, we would sit for hours and hours in front of a computer and then just give the piece away without ever seeing it again.

There were two goals with Hamill: First, we wanted to work in the real world with our bare hands which had to implement experimentation so it wouldn’t become boring. Second, we wanted to expand the experience beyond the screen. In order to do that we had to build physical things, and building physical things defines experimentation because it’s not as easy as working on a computer.

Experimentation is a big part of our production process; we leave space for things to fail and to discover what is interesting. Oftentimes you think the machine will work exactly as you think it will. But when you put things into reality, reality hits back, and when it hits back sometimes it can be painful. You have to look at what the idea or concept or thing you are building is actually saying. We keep our minds open as projects mutate a lot during the experimentation process, and often you will get a jolt of an idea or a new concept you want to trade. When you build things you encounter problems, but you also en- counter phenomena that you would have missed if you weren’t open to the experiment.

So would you classify Hamill Industries as an artistic or commercial practice?

We started Hamill Industries as an experimental work- shop with no intention of becoming a full-time commercial practice. It was a creative need to fulfil more than a business one. But now brands and companies are interested in what we do because we treat it as an artistic process. We work mostly with the creative industry, like musicians or institutions and festivals for installations; but we’ve found success working with brands.

It’s interesting. When you work with brands it’s like, they have a problem, you pitch a solution and they decide the rest. Hamill is the other way around — those brands see what we do and say ‘that’s interesting, I want that’. When that happens it’s easier to communicate because they are willing to be a part of the process and understand it. But we need to communicate that process in the beginning to be very clear that what we start with may not be what we finish with.

Going back to your work with Sam [aka Floating Points]. To me this seems like the perfect combination of your skills and ethos, and his artistry and ambition. He is so aggressively experimental and clearly pushes you to do so as well. Can you talk about how that relationship has developed over time and how it pushes both of you forward?

Sam is like the third member of Hamill Industries. We met amongst friends and he saw some things we were working on, and I guess he loves weird things and analog things so we clicked instantly. He asked if we were interested in doing a music video and had this idea around light which eventually became the video for Silhouette’s. That was nice because he had released other stuff but this was his first LP and was a big departure for him; at the same time we realised this was an interesting way to work where he kept feeding us interesting inputs. Eventually, it became a long-term relationship in which he is a very active part — sometime’s he gives us ideas and often he just gives us space to do what we want to do. It’s very inspiring to work with someone that has that trust in you.

He is a big deal in the music world and we’re not as famous, but we’ve grown up together and the relationship has evolved to create even more radical things. As I said, his music is hugely inspirational because these are very handcrafted compositions that tell a story. And the way he creates his sounds and the machinery he uses is so analogue and very experimental, which is how we work as well.

For example, with this last tour, at some points during the live performance he takes over control of the visual setup and creates music for the eyes. He would play music by watching how the visuals would react to it, and now a big part of the show is where he just takes control of every- thing and creates music according to how it looks. It’s very synaesthetic. And again, you’re not playing music or making visuals for it to just look and sound nice, you’re playing it so everything can be together and tell a story.

I’m very intrigued about the inputs that go into your work, because while it’s very much defined by technology and machinery, it’s also incredibly organic and textural.

The influence of the natural world is everything to us. We take inspiration from phenomena in nature, from light refractions to sound waves or sound being transformed into a pulse. Everything is nature, and one of the main reasons we do ‘real’ things and make stuff and assemble it with tape and fill it with digits is because we want things to feel real. It’s something we want to run through every project so that it feels real, and alive, and moving with textures. We also don’t like to hide anything, we reveal the machines in a very natural and organic way.

For instance, say we use a green laser in a nightclub. This is a machine that produces light, so why can’t we use that in a way in which we can feel it and sense it and watch it and almost touch it as if it were regular sunlight? This natural physicality is very important as an aesthetic goal when working with technology. We don’t want to make this separation between technology and art and nature; everything is part of the same natural phenomena. There is no difference between them.

A laser is, by its own nature, not often willing to be manipulated, so you’re really bending a synthetic force against its will. Is that transformation of technology into a natural form difficult to achieve?

There's always a way. We have this thing where we don’t fear trying. Often when you’re working with processing, programming, or with specific software or hardware you say ‘oh that’s too sophisticated, I can’t do that’. In the internet age, we fear not knowing everything. But we’re like ‘I don’t care, I know we can make it. We’re going to find a way to manipulate it even if it’s not the correct way’. So yes maybe a lighting engineer would use a laser differently, but our lack of expertise means you see the technology in front of you in an entirely different way.

And thank God for the internet, we wouldn’t be anywhere without it and for everyone who shares their research and code and information. It’s part of our practice to share that knowledge back as well. Once you’re deep enough into a project you are usually capable of understanding how things operate. It might take a bit of abstraction and it’s not going to happen just by watching a tutorial on YouTube, but the knowledge is there and the capacities are there, you just need to break through that invisible barrier to solve the problem.

In one of your projects you ran the mathematical algorithm of a black hole into a laser to create a visual projection. How far into space and time does this go for you?

Reframing what it means to be human is a recurring theme of ours. We love sci-fi movies, we love art and literature inspired by the universe. There’s a concept Pablo calls ‘human-cosmic-vertigo’, where you feel small but also great; you belong to something but you can’t understand what it is but you know it’s there and it’s overwhelming but really beautiful. The idea of using the laws of the universe to inform our visuals is there all the time because we have this overwhelming feeling of belonging, and not knowing while also finding it beautiful.

This book is about restlessness and the forces that continue to push us. How emotionally driven is the work from yourselves personally?

There is always that ‘eureka!’ moment of something you want to pursue. Everything for us is about a fascination with something: ‘I want more of this. I need to know more’. Then it makes sense with the story that was in your head. Sometime’s that story is an image a collaborator has given you, or sometime’s it comes from your own desire to explore an idea like human-cosmic-vertigo, or the idea of a song as super emotional even if it doesn’t necessarily sound like it.

Sometime’s an emotion will trigger an idea and some- times an idea is what triggers an emotion. But emotion is everything to Hamill. We are a family, we work as a family, operate as a family, it’s all based on emotions. We just couldn’t do a project if we didn’t feel excited or fascinated or interested about it.

What are some of the phenomena you haven’t explored yet that you would like to?

There is so much. We’d love to work with gravity, with magnets, with vortexes and things that move very fast, wind flows, thermal camera, infrared technology, bigger motors, bigger robots...

Obviously that technology is expensive, so you have to find the right project or idea. It’s like I said earlier, things can be beautiful but they need to mean more. It has to tell a story and have a reason for existing. We’ve been trying to use these technologies but it doesn’t always work because the concept was not ready for it. Story and emotion always comes first.