The sharks are free-range and Michael Muller is out of his cage…

The VR filmmaker, adventurer, A-list photographer (arguably best-known for Rihanna’s Unapologetic album cover and many Marvel movie posters) and Semi Permanent Auckland speaker is on a mission to put sharks in schools, virtually, and really change the planet for good.

In the corner of a Los Angeles classroom sits a pair of ClassVR headsets that have only been used twice because there isn’t the content. It’s the classroom of twin girls whose father, Michael Muller, is about 17,500 kilometres away, swimming unprotected through the deep blue of the Indian Ocean, keeping company with great white sharks, because he wants to change that. Actually, there are a few things Michael wants to change.

Almost every year from May through July, schools of literally billions of Southern African pilchards (known colloquially as sardines) spawn and make their way north along the coast of Southern Africa, sometimes in shoals more than seven kilometres long. Dolphins round the sardines up into bait balls – like border collies herding sheep – sparking a feeding frenzy by sharks, game fish, whales and birds.

There’s a lot of blood in the water, and Michael Muller is there amongst it all, doing what he can for the planet, with only his cameras for protection.

We are at a critical time in history,

says Michael, Marvel’s go-to photographer – think ‘Deadpool’ and ‘Captain America: Civil War’– now turned virtual reality film-maker.

“Half the Great Barrier Reef is gone and we have a plastic island the size of Texas adrift in the oceans. I’m thinking about my daughters not seeing some of these animals. What we do now will have a huge impact.

“As storytellers, we can document these things and tell people about it – with VR we can actually let them experienceit, because the world needs to stop and pay attention to what’s happening.”

Bringing the monsters of the deep into the classroom, workplace and cinema might just help shift the tide in the planet’s favour – but it’s tougher and less glamorous than it sounds.

Unlike the adventurers of yesteryear, who were often more concerned with killing and conquest, today’s adventurers – who, like Michael Muller, are often designers, artists and inventors – go to observe and record in the hope of preservation and protection. To do so they drag tons of high-tech equipment along with them; it’s often stuff they’ve designed, invented or even cobbled together.

Talking about his first virtual reality film, Into the Now, a story about sharks and the man-made threats confronting our oceans that premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival, Muller says he wanted to move the VR genre along because it’s been stagnating.

“People plop a camera down on a stick and leave it there and they think that’s interesting. I wanted to make a feature film – the first feature film in virtual reality, and to do something that hasn't been done before. That said, I always stay out of the result. I just think big about an idea I have and I go after it – you can’t afford to think about the obstacles. If you have a vision or an idea, don't stop until you have created it. Don’t stop until you’ve got it out of your head.”

Muller quickly realised, however, that much of the technology needed to achieve what he had in mind didn’t exist. At every turn, people also told him it couldn’t be done. “Mobile devices can’t handle too much compression in VR,” they said. “Nobody watches ten minutes of VR, never mind 30 minutes – all they can handle is three minutes, max.”

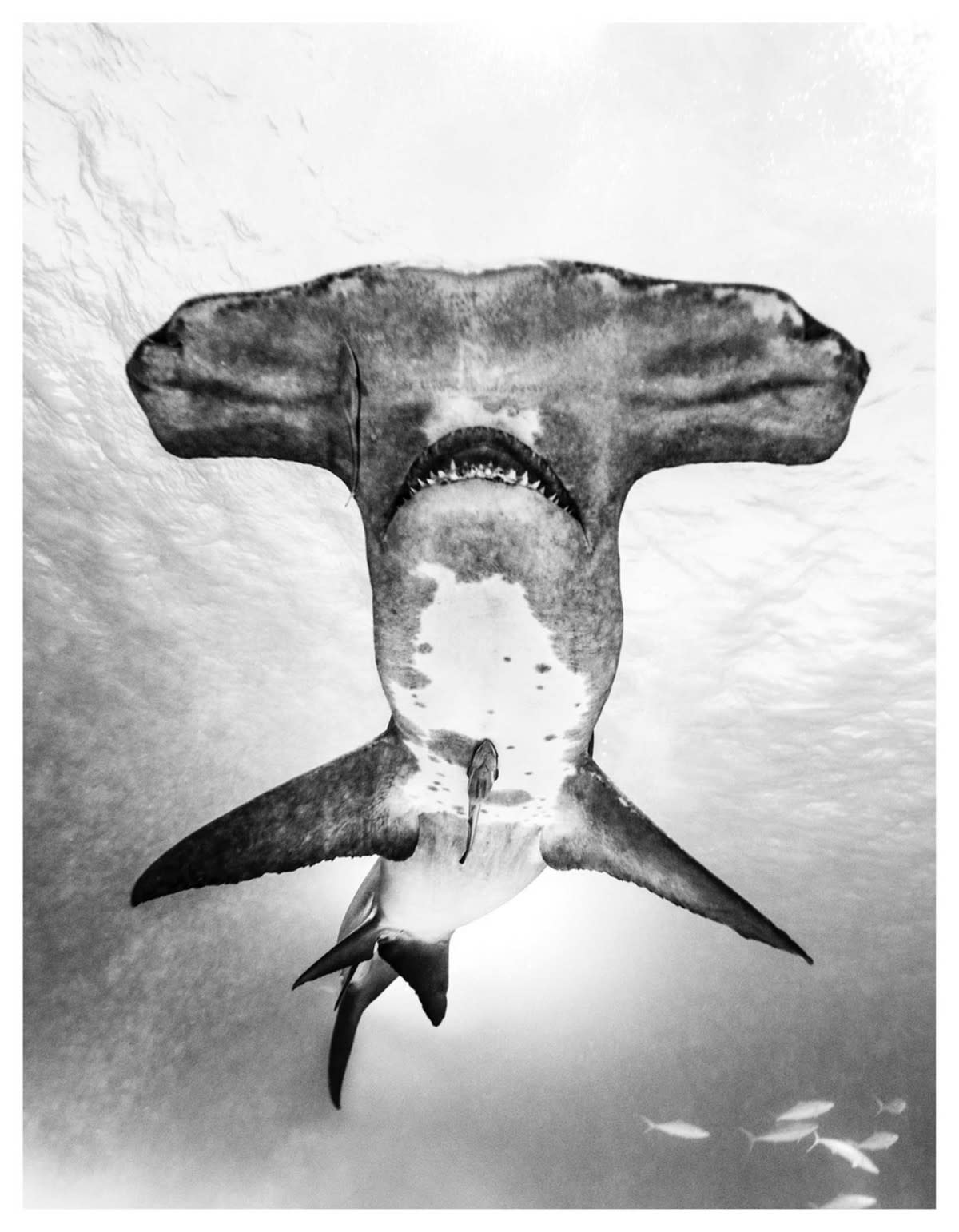

Muller’s response was, “If you want to be an artist, and you want success, you can’t give up at the first roadblock; you’ve got to keep your eye on the prize – to keep trudging towards that goal. It can take years from the time of conceiving your vision – for me it was a shark coming out of the light – to having the finished piece in front of you.

“Where nature photographers use natural light, I wanted to bring studio lighting to the sharks, which meant I had to take the studio to the sharks. I assumed the underwater lighting I needed existed, but it didn’t. Then somebody who said he could do it ripped me off; he gave me a metal box. I'm not an engineer, but since I couldn’t find anybody who thought it could be done, I had to invent it myself. I fabricated these 1200-watt strobe lights, the most powerful in the world – today, we have four patents pending on them.”

Right at the start, Muller realised Go-Pro 360s weren’t going to be up to the job, particularly since he wanted to shoot stereoscopic, because he was shooting for the future, at resolutions the future would demand.

“Together with the guys from VRTUL we came up with a system using nine Blackmagic large-format cameras – each weighing about 55 kilograms – to shoot in 4K Stereoscopic 3D. It’s the first stereoscopic footage shot underwater ever. Imagine taping three McDonald’s trays together and trying to push them through the water in the swimming pool. Well, our challenge made that look easy.”

With the naysayers lying in his wake, obstacles and objections overcome, the biggest challenge remaining is to convince viewers that they don’t have to look straight out in front of them. Now, it’s up, down, around, backwards – a 360-degree experience that’s all on and completely unexpected. Sometimes getting people to expect the unexpected is the challenge.

“That’s what you can expect from me at Semi-Permanent in August,” says Michael. “The unexpected.”