Tides and cycles

Not so much in its challenge to Australia’s contemporary cultural identity (something he is largely known and regarded for), but for translating those ideals to landscape works inspired by the far South Coast of New South Wales Australia. The result, a 21-piece exhibition at the Bega Valley Regional Gallery, chases freedom, the tide and slow looking. The effect on him, profound as it may be, is outlined in our interview below.

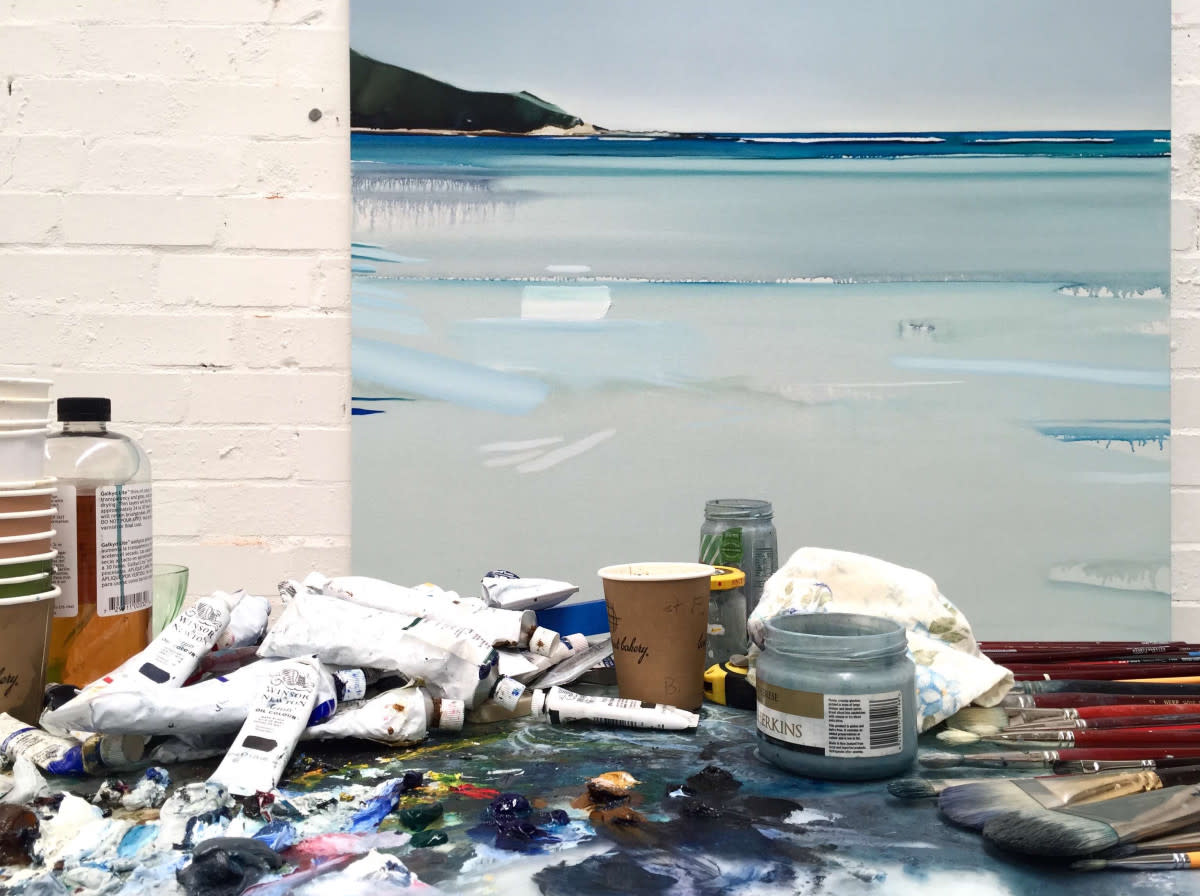

Feature image by Nick Walker

When you look back at a career spanning over fifteen years, how do you feel about your decision to pursue art full time?

Looking back into the lens of decision making is always dangerous. As a young boy, painting was something I wanted to do desperately and was finally prepared to leap for as I got a bit older. Art is not one of the smartest career choices on a lot of levels, but it is one of the most beautiful, and when it works you get to create each day, have a voice, and be part of a world full of passionate and interesting people. I feel pretty damn lucky to roll out of bed each day.

Has your technique changed in the shorter term?

Definitely, and I hope that keeps changing. I don't want to make the same paintings I did five years ago. I like to think of painting as a voice, and as you mature your voice changes a little bit. As the years pass you go deeper into your practice, you keep discovering through risk-taking and you feel like you're pushing further which is what you need to do to keep the rush that you get from making a good painting. You can't revisit the magic of past moments.

Your new show, ‘Inlet/Outlet’ came about from an artist residency in the deep south coast, can you run us through the experience of putting this together?

Recently I was part of a still-life show at the Bega Regional Gallery. While I was there the director of the gallery (Ian Dawson) proposed an idea for a residency that he wanted to do annually. I was lucky enough to be the first artist to receive it.

I travelled to Bega without many expectations. Residencies are great for artists because they sling you out of 'groundhog day' and make you think differently. New environments are critical for sparking new ideas. I turned up to this unique house in a national park, very secluded and isolated, no reception, a beautiful pristine inlet on a strip of a coast I'd never visited before. It was a 6-hour drive to Sydney and the landscape was magical. It also came about at a really important time of my life; I went with my wife who was pregnant at the time, only a month or so until the arrival of our baby boy which was a momentous change for us and a special time for us to sit off the grid for a few weeks.

Did this immersion into a new environment cause a dramatic shift artistically?

Something weird happened to me down there. I wanted to let go. My style has always been pretty controlled and as I've gotten older (and as many artists do when they age) I have started to celebrate the paint doing more of the work; being more free and bold and having stronger marks. When you look at some art students, they dab away nervously and kill the beauty of spontaneous marks. I think becoming a father was critical for me to start giving in to forces far greater than me.

I produced a lot of watercolours while I was there. The National Parks Association weren't too excited about me using oil paints as (rightly so) they are serious about protecting the land. But [the watercolours] allowed me a spontaneity that I had been missing. I wanted to translate the freedom of these watercolours into larger oil paintings, so that became one of the aims of this show.

Becoming a father was critical to start giving in to forces far greater than me.

Julian Meagher

I’ve always enjoyed your allusions to modern Australian identity, particularly through the depiction of objects and iconography that could only be recognised here. How do you achieve that through landscapes?

Interesting question. I've always been pretty fascinated by our collective cultural or inherited history of what it means to be Australian, not quite knowing who we are while growing as the country does. There is an identity challenge we all face of what it means to be Australian, and I've always liked to find objects to bounce that idea around. Painting landscapes as a white male, you can't stop thinking (as you stand on a point or a beach or listen to the forest) about your relationship to country and your history within it; what we've done wrong and what we need to do to start reconciling previous colonial failures. These things are always in the back of your mind as you paint the Australian landscape; it is a very loaded and symbolic subject matter.

You mentioned before the isolation of your residency, did the lack of constant information (from mobiles and such) change your process at all?

I think it was just the slowness. Life for me just seems to go faster and faster and that's not always the best thing for an artist. Sometimes you want to look at things for a few hours before you start painting. We live in a world of such immediacy and impatience that art is one of the last remaining crafts that involve the hand; slow observation, going back before you go forward, that's all a beautiful part of painting. The isolation allowed me to think more about that and long for that slower speed of working.

My day was governed more by the tides than by a watch or phone. That's a rare way to live.

Julian Meagher

Would you live permanently down there?

I'm now back in the city, finishing this series in a hot warehouse in Marrickville next door to a cheese factory and a brothel. I'm hanging onto the silence of nature and the ring of bellbirds as the soundtrack of the day; no phones buzzing or texts coming in, fishing for hours, watching the tides come in and go out.

I spent a lot of time fishing. When you're doing a residency you don't necessarily spend all your time painting, it's also about reflecting and absorbing. I've had a lot of more senior artists say 'just stop for a second, you'll make paintings later so don't try and make a whole bunch of work during it’. Fishing was important, it's one of those pursuits that makes you stand and look at the water for hours. Normally you watch the ocean for 20 minutes, then say 'let's grab a coffee' but fishing forces you to think more about cycles and nature… your time is not governed by a clock. When it’s low tide, it's good to catch bait. When it's high tide, you wait and see what you can get. Chance plays its part in every event. My day was governed more by the tides than by a watch or phone. That's a rare way to live.

It must be impossible to translate that isolation to your city environment…

It is impossible. But there's that feeling…something changed in me while I was there but I think it was related to not being a slave to the phone or a clock or timetable. It was a special time for everyone and made me really think about cycles, and that's the key thing I want the show to be about. It's titled 'Inlet/Outlet'… smaller cycles in nature being part of larger cycles; the personal ones and the collective ones that we all live in. Living in the city, you don't feel cycles as much. You don't see the stars. We have really vague seasons too, we don't have much seasonal symbolism, but when you're in the bush they are all around you—the environment is on your skin. We don't see that enough — things being eaten, trees sprouting and dying, all those motifs of cycles and nature — that’s what I am trying to hold onto.

Life chases you no matter where you run. It makes you think differently, you see poetry in everything if you are looking and that excites you to start another painting…

Julian Meagher

I’ve heard that you’re not a huge fan of art on digital platforms like VR. Did you want to elaborate?

I really struggle to fall in love with the change in how we communicate. It's amazing in the sense of access to information and speed to contact people, but I don't think we have acknowledged the damage it does. We have all become slaves in a way to technology. The immediacy we expect in every aspect of our lives from our food being delivered to people answering their emails to returning submissions, where's the time to breathe? It's sold to us as this idea of 'your life will be fuller and more convenient with these tools’ but I feel like life is pretty fuckin' full already. We'll look back in 30-50 years and the black mirror will be the cigarette of our generation.

As an artist it’s not useful to answer my phone mid-way through a painting. You need to be present. I was talking to an art collector the other day who asked me 'how come video art in the 90s was the biggest thing and painting was dead in a sense, yet now painting has made a huge comeback?'. It wasn't necessarily cool to be a painter 20-years ago, but now it is slightly coveted. People miss the hand of someone that's made something and the whole bespoke, grind-your-own-coffee ideal has become quite longed for because we don't use our hands to create as much anymore. You don't see the human in items very often, but in a painting it's so evident; you can see the brush-marks, the colour choice, you can almost be there in the moment when they were painting it.

Every painter works differently and that’s the beauty, you're actually seeing the human in it. The tech giants can argue all they want that the person is still in it, but the device dilutes it. That's how I see it anyway.

I’ve also heard you say that you’re not particularly motivated by money. What gets you out of bed in the morning?

Who’s been telling you all this? I am financially motivated in a lot of ways, without paying for my studio I can't make paintings, so we all need an amount of money. But how much money do we need? The more money I make, I'm not a happier person. But if I'm making good paintings and spending time with people I love…what else do I need?

Artists are also great at spending their money on ideas they'll never earn money from. We aren't paid per-hour, we don't expect to sell every painting, ideally, we make work for all the right reasons. Being broke, however, is a great motivator, and being fearful of not being able to buy food for your kids will make you paint like a demon, but there is still a selfish purity on the journey. It ties back into the question of ‘should we even be selling art?’. The commerce of art is an interesting subject, it would be ideal if it wasn't sold at all, if it were instead traded or gifted or made for non-commercial reasons—that's how it's designed to exist. But the reality is that it is often filtered through a marketplace.

Living in the city, you don't feel cycles as much. You don't see the stars. We have really vague seasons too, we don't have much seasonal symbolism, but when you're in the bush they are all around you—the environment is on your skin.

Julian Meagher

So after this show, what’s next?

I have to survive this one first. I'm good at planning my next holiday while on holiday but I'm so deep in this show at the moment that I'm just focused this series. It's often in the last few paintings of a show that I start to get a vision for the next one. They all lead into and speak to each other, it's not planned out for me.

Would you immerse yourself in a new location in the same you did down in Bega?

That’s the fastest way to leap forward in your practice, shake it up a bit. Driving to a warehouse in Marrickville, I'm not going to have too many lightbulb moments, so I always hunt down new areas and experiences. I always have a few months of creative silence after a big show, quite a bit of 'what the fuck am I going to paint' but I still turn up to the studio each day and push through it. I didn't expect this residency to have as profound an effect as it did, and maybe timing had something to do with it. Events happen and we respond to them. Life chases you no matter where you run, it makes you think differently, you see poetry in everything if you are looking and that excites you to start another painting…

Inlet/Outlet opens at Bega Valley Regional Gallery on February 23, 2018