An interview with Oana Stănescu

Oana Stănescu is a Romanian architect who runs her design studio from New York City. She was most recently nominated as one of Coachella's 2020 installation artists and currently teaches at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

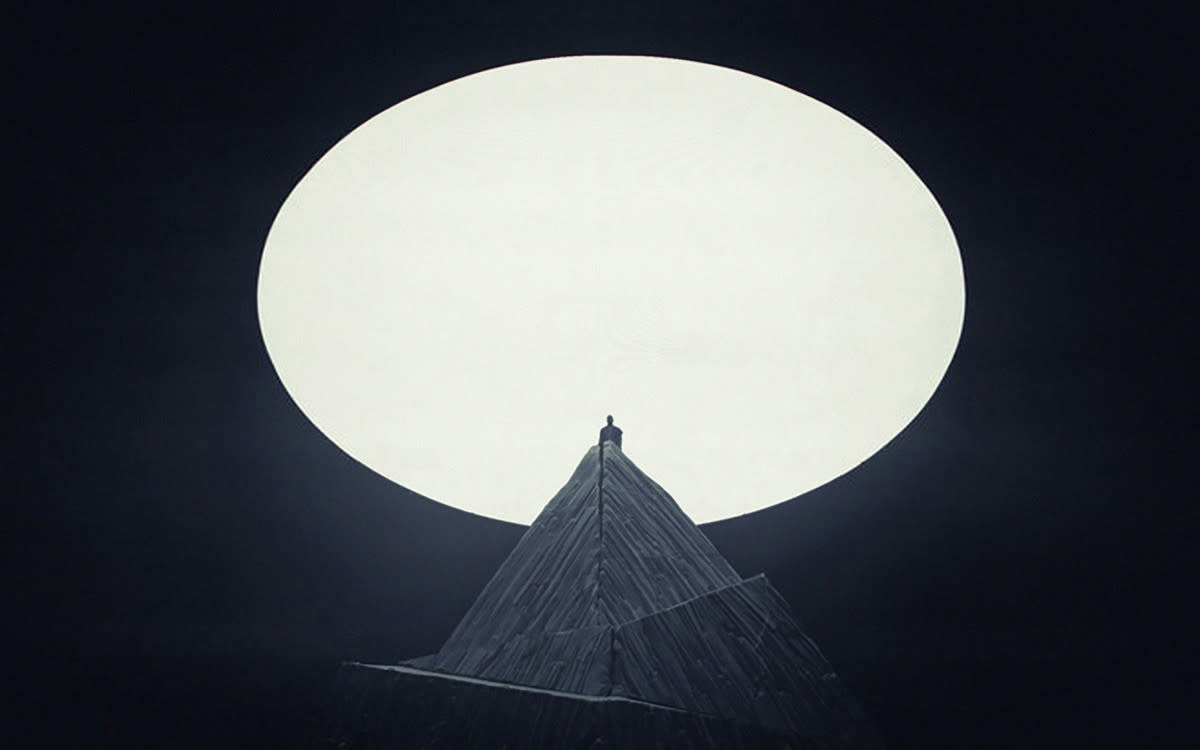

Feature image: Off-White Singapore

Hi Oana! The depth of your portfolio suggests a real pursuit of new ideas and approaches. What does the word ‘restless’ mean to you in the context of your work?

It means staying curious and always having a willingness to learn. It has a lot to do with accepting that you’re never in total control, so the only way to stay sane or make something out of it is to keep evolving and accepting your lack of control.

The notion of being comfortable or laid back is just not interesting to me because there is such little growth or evolution there. I'm also less interested in repeating myself. What's the next challenge? What’s the next thing you can grow towards? For a metaphorical translation it’s like hiking a mountain peak, then getting up there and seeing the next peak and repeating that process.

There are never two moments that are the exact same in our lives. We often chase moments of nostalgia, but accepting that everything is new is super exciting to me because it presents new opportunities to make something of it.

I’m sure you get asked this a lot, but how much of an influence did your childhood growing up in Romania impact your career?

It had a huge impact. Something that I wasn’t able to fully appreciate until I got a little older was that I experienced the downfall of a dictatorship. Someone who was seen as a god one day was nearly shot live on TV the next, and all the structures or authority I took for granted as a kid fell apart with it. It gave me a very healthy distrust of authority but also of institutions. You understand that everything can change very swiftly, even for dictators. You also learn not to rely on governments or institutions to give you anything; you have to make your own bed, your own world, your own everything.

I always think back to my parents in that world, and how we grew up in the same spirit of doing things so we wouldn’t be bored. There were no cinemas and only one TV channel, so we would go up in the mountains and snowboard or hike. It was very proactive with this notion that if you wanted something you had to go out there and get it yourself.

In retrospect I’m very grateful because it put the agency on me. It’s very freeing to have limited expectations of the world around you, but that freedom comes with responsibilities and I had to learn that it was only in my power to build or achieve anything. But I also don’t believe (in a naïve way) in the world. One does requires a healthy dose of chance so it is still surprising when things do indeed work out.

One could probably argue that architecture is one of the most structured disciplines there is, in terms of hierarchy and expectations and ‘starchitect’ and so on. Was that ever a challenge for you to navigate?

I didn’t discover architecture until I got into college so I had no idea what I was getting myself into (which is partially why I chose it).

When you first start you’re learning and just excited about anything and anyone, and all this information that uncovers this universe. But it’s important as you evolve to ‘kill your idols’, as they say. We are only able to get where we are thanks to those who laid the groundwork, but you need to aim higher. As a young woman, particularly a young student in Romania, you didn’t grow up thinking ‘oh, I want to be a starchitect’ because there was no room for anyone or anything like you. That and the innate problematic nature of that term.

I was lucky to work with some really amazing offices and incredible mentors that were hugely insightful, but there comes a point where you have to make your own choices. I was lucky to be given the agency to learn about myself and understand what I wanted or didn’t want to do; the things I care about vs. the things I don’t. And my peers all grew up during the financial crisis in 2008, so we witnessed [what could happen] firsthand and decided to take very different paths.

Now looking at emerging generations, they want to change things even more dramatically. There is this notion of the architect having one job for decades, and it’s harder for younger generations to imagine themselves in these long-term commitments because the idea of ‘long-term’ is very ambiguous these days. Everyone is so terrified about the present that it’s hard to think ahead, so they have much higher expectations from the work they do today. We’re not as willing to bank on an uncertain future because we saw older generations do that and it didn’t quite work out for them. We have different goals. And that’s exciting because it means it’s time for a change and it’s in our hands to take the reigns.

On that note, you teach at Harvard which gives you an opportunity to teach the next generation how to navigate those structures and anxieties. What do you think is your goal as a teacher?

If anything, I see myself as an instigator for their goals. I’m really excited about the students and learn a lot from them because they’re the first generation that grew up with very different tools. I don't think they fully understand the unique world view they have. Even I feel outdated compared to how they see the world, and I’m probably one of the closest architects in age to them.

With the younger generation [of architects], there's a lot of soul searching. They're struggling with this ‘myth’ of the architect as some white-haired god sitting at the centre of the matrix. The reality is that we’re a service industry at the mercy of a lot of currents and we’ve been acting as such for a long time now.

The soul searching is around the question, ‘what are we making out of this?’ The fact that architecture is a profession anchored in the past with a foot in the future gives us the ability to solve incredibly complex problems in a creative manner. I think it would be more fruitful to focus on the scale of solutions instead of worrying about about architecture is vs. what it isn’t, or at least consider how the skill set can be applied in collaboration with other fields.

I’m always interested in the multi-disciplinary aspect of architecture because I feel we’re reaching the tail end of hyper-specialism and pioneers in narrow fields. The only way to ride those waves of change (which will come faster and faster) is to adapt. It’s the most crucial skill one can acquire. If you look at the data, it says the skills you learn in school are obsolete by the time you turn 40 which for many people is only a decade after they graduate. So how do you prepare for an uncertain future? It takes a lot of looking at oneself and understanding the values you care for, then going with it as opposed to holding on to outdated ideas of what the job means to them.

Last time we talked you mentioned you wanted to work in a space between art and architecture. How did you go about learning the artistic skills required to do that? It can take so long to get into a position where you could create anything near the first thing you were inspired by, even if you’re still interested in it by the time you get there.

There has to be this audacious optimism and a sense of just going for it. The other important thing is a willingness to fall on your face because if you don’t take any risks and are looking for all the information before you try something you will never get anywhere with it. The only way to become good is by doing it.

We’re so concerned by how things are perceived or judged and the exteriority of things. When I look at my idols, I realised that behind the genius was the fact they just did things and pursued ideas, and things went wrong and things failed and that’s part of their narrative too. But what I admire most is the ability trust that you don’t always know where something is going to go, and the courage to really just follow your own, seemingly impossible path.

Can you talk about the decision decision to break up [architecture studio] Family and start your own studio?

That decision that came naturally through some parallel experiences. I had a gone through a big health scare at the time—it wasn’t something expected by any means, but it was thrown my way and the ball was in my court to make something out of it. So I chose to take some time off. I didn’t work for a while and took time to recover, but I was also reading and running and eating and spending time with friends, and I realised that was a luxury we don’t typically afford ourselves in our mid-thirties. It’s unfortunate because it was an incredibly revelatory time, almost to the same degree as that lust for life you develop late in high-school. It’s also hard to come back from when you’re on the daily grind of professional life.

So over the course of a year I hit the brakes and took things slowly, then in the next year I started pushing the gas because that appetite had returned, as well as a new direction I wanted to go in. That also had a lot to do with acknowledging the things that hold us back. We’re not aware of our own fears, and we don’t understand the things that matter to us. I became more comfortable in the pursuit of my own ideas and values and what seemed interesting and fun to me. And I felt more removed and freer than ever from the external world, the perception, the feedback. Its value was nowhere to be found in the crucial moments of my life, which was very liberating.

Did that period of time express itself at an aesthetic and functional level?

Absolutely. Since starting my own studio, I haven’t been interested in a specific style or aesthetic, I’m more interested in the idea and an insistence on radicality. Something else I’ve been trying to do more is to use projects as an excuse to have conversations with people I admire. I’m working on a house in Toronto with my good friend Keith Burns, I did a project for MoMA PS1 with Akane Moriyama (a fabric artist I met two years ago)… it’s really about focusing on enjoying that 99% process rather than just the 1% outcome, and enjoying the conversations and the value of the time spent with people in the pursuit of these ideas.

And that in turn invites a conversation with the audience too?

Yes. Something else that happened when I started my own studio was acknowledging how all the different interests and aspects of my life could be tied up in a seamless way. There is no line between the book I’m reading or the song I’m listening to or what I’m drawing; it’s all deeply interconnected. That’s really exciting and ultimately reverberates in the architecture of a project.

There are two things I’m interested in with my work. The first is that I think of architecture as an infrastructure that is enabling something; life, a concert, an experience... It’s role doesn’t need to be ego-driven. It can’t be just about itself. Then it’s interesting to see what that can unlock and what it can enable.

I’m also trying to ask what is the minimum you can do to get the maximum results? The world today has us striving for such big gestures that we’re desensitising ourselves. The most powerful experiences aren’t necessarily about ‘a lot’, they are usually tired to very simple experiences, or gestures or moments. So I’m trying to pare things back down to the minimum required to achieve a big effect.

The work does seem to subvert the role a project plays in its environment—it’s not just a pool, but a water filtration system; it’s not just a bridge but a work of art; not a retail store but an invitation. What is the role that technology and nature plays in your work?

There is nothing more influential than mother nature when it comes to inspiration or design. There is a lot to learn there. But it also depends on the circumstance. For example, I’m working on a house in Canada called Long House, which is just that—a very long house in a straight line—but it’s in contrast to the scenery around it. So it’s this simple gesture in relation to the hyper-organic natural reservation it sits in.

I also take a lot of inspiration from hand-sketching. After you gain a certain skillset, at some point you are at the mercy of that skillset. Quite often I just try and mess things around and diversify, whether that means picking up a pencil or changing the software or finding new tools to do things different. I just want to play around and see what else I can discover.

Design is a discovery process. If you know what you’re going to do, it probably means you’ve done it before. So it’s good to know where you start, but then just go along for the ride. It’s like snowboarding down a mountain, you know where you’re going but you’re not quite sure what you’re going to experience along the way, what turns you’re going to take and how it’s all going to feel—usually, it’s better than what you could imagine.