Behind the scenes of a Chemical Brothers live show

The work of Adam Smith and Marcus Lyall is a portfolio of sensory superposition; dual waves of science and creativity designed to scramble your neurons and bring you to rapture.

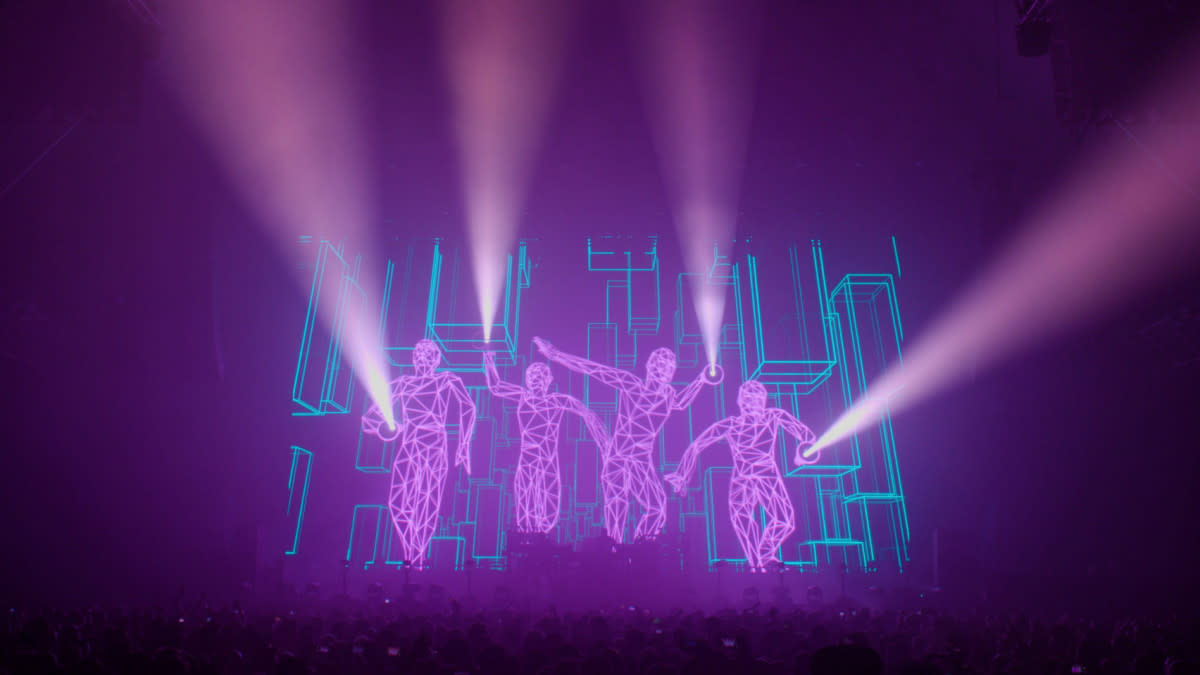

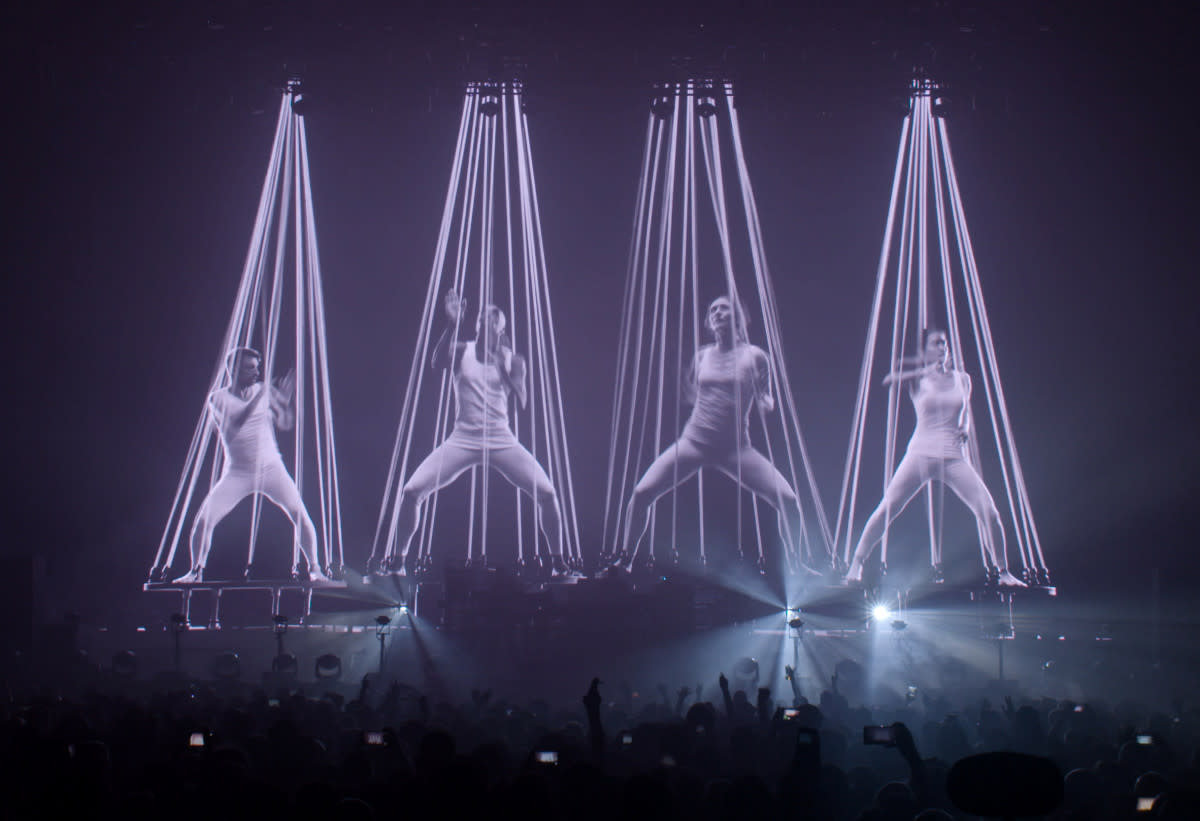

For over two decades, the pair have directed the psychotropic visuals for The Chemical Brothers' jaw-dropping live show (one of the more visceral experiences electronic music has to offer), staged on an impossibly sized LED screen behind an equally staggering amount of synths and tech. The show itself is as much an acid trip as open-heart surgery — a research piece worth of colour theory, technological horsepower and live-action filmmaking that exacerbates the thundering sounds coming from the speakers below (if the tech prowess doesn't do it for you, the giant laser-shooting robots, menacing clowns and Japanese superhero characters should fill the void.)

Before The Chems bring the game-changing live show back to Australia for another round of telegenic mayhem later this year, Smith and Lyall (who also directed several of their music videos as well as individual credits on shows like Skins) gave us some insight into the psychology of raving and their surprisingly handmade design process.

You've been working with the Chemical Brothers for over 20-years now, but were both involved in the DIY techno scene prior to that. What do you think are the fundamental aspects of a good party regardless of scale?

Adam Smith: Sweat, strobe lights and euphoric unity.

Marcus Lyall: There is certainly enthusiasm for doing stuff that trips people out a bit. When we started doing visuals there was always a sense of fun, like ‘what if we tried this thing. That'd be pretty weird, wouldn't it?’ Coz that’s the whole bit about this rave thing, the feeling of ‘well we can do anything can’t we?’. There are no adults telling us no. We’re creating a space and inventing images that we think are gonna do something to the audience. It’s nice that at this point we’re still given that permission to play.

We went to the production manager and said 'can we have some giant robots on stage?' And the first words that came out of his mouth were 'can they have lasers coming out of their eyes?'.

Adam Smith

Would you say you’ve built a body of work with an overarching narrative over the years, or is it more responsive to the technology and attitude of the day?

Adam: The music always comes first, then we’ll see what technology we can use to enhance it. Something we’ve been trying to hone in the last two or three tours is the relationship between what’s happening on screen and what’s happening on stage so the lights can physically interact with the visuals. But there are still the basic rules of projection: shooting on black background, not having full-frame visuals so it seems more mysterious; bright, saturated, high-contrast colours etc. There are smaller situational things that inform us, whether it’s a 12x9 foot screen 20-years ago or a 15x15 metre LED screen today. But it’s the human connection that still holds true.

I think what separates the show from a lot of others is that the majority of what we make involves people, and a lot of it is filmed. There is some CGI in there but not as much as you think because we’re trying to use technology in an organic fashion. But that’s what brought Marcus and I together — my current job is directing a BBC drama and Marcus makes incredible installations based off human psychology. Those sensibilities and interests merge and influence each other and those nodes find a way into the show.

Marcus, a lot of your other projects involve an exploration of neurology and creativity. Can you talk about how that thinking influences you in the context of a live show?

Marcus: I'm definitely interested in human psychology; I'm working with a neuroscientist at UCL at the moment. I've gone to psychotherapy for years and it's incredibly valuable, just that thing of letting the unconscious out a bit. This isn’t cutting edge — a lot of it is looking back to the 20s and 30s but the concept of being unfiltered about ideas has been very helpful.

The Chems show is more closely aligned to Jungian psychotherapy and the idea of archetypes — characters that represent something, like a feeling. That's very much involved in what we try and do in the show, inventing characters and situations that sum up the feeling of what the music is doing or what the lyrics are saying in a way that isn't too literal. You’re not prescribing an idea but keeping a dreamlike feel to it.

There are definitely some visual things you can do which have a strong effect on the brain.

Marcus Lyall

Adam, you said in a prior interview that a lot of this show is about ‘repression and release’ which I think is a nice analogy for why we go and experience these things in the first place. What does that term mean for you?

Adam: The visuals for [the song] Galvanise perfectly encapsulates what you’re saying; that was an exploration of what it means to escape and be free. On a personal level, I’ve always struggled to be free enough to just ‘be myself’. That conditioning (whether from society or school or whatever) meant I always craved the freedom to just ‘be’ and I fought a lot of systems to do that. It’s the music as well, all the visuals come from the music and the music builds you up and up and up, and then it releases you.

That’s an analogy for a lot of people’s lives and why it connects — it’s making it more personal y’know? When we’re in the freeform ideas stage we try not to question anything too much, it’s just connected to a feeling that’s good. Take the visuals for Got to Keep On for example. We were playing the track loud, then I just started strutting about, which is not my usual demeanour. But it felt really right, and maybe it was a part of me I wanted to express. Then we thought ‘maybe we could do a catwalk show!’ Or the visuals for Eve of Destruction was just immediately thinking about Japanese superhero television. There are just those instinctive moments. The robots are a good example of that too.

Adam: My Mum had a big collection of tin toy robots, and that’s been in the show for quite a long time and has been a popular motif. So we were talking about how to do something physical for the show and Marcus was like ‘well I suppose you could make the robots’ sort of as a joke because there was no way. But then we were like ‘well why not?’

Marcus: Touring this show is a logistical nightmare, but we went to the production manager and said ‘well, what do you think about some giant robots on stage?’ And James, bless him, the first words that came out of his mouth were ‘can they have lasers coming out of their eyes?’ And we were like… ‘yes, great idea. That’s good’. Then it’s just had this sense of fun around it. We found these amazing guys who build props and were getting technical drawings, then people are working out how to get them moving around and animators are giving them expressions. When the robots turned up to rehearsals, the whole crew stopped to take a look. That comes back to what you’re saying about being free to connect with the flow and uncensored creative freedom. Once that idea is formed, it’s about using the other side of the brain to bring it to life.

Adam: It’s a testament to [Chemical Brothers] Tom and Ed that they’ve allowed for this play and freedom to happen and to make it a part of their show — the resources they put behind it could easily be going into their pocket. They’re truly giving the audience the most full-on sensory experience they could possibly give.

I think the biggest misconception with the show is that it’s made solely for the person who is off in the corner tripping their head off. Who do you design the show for?

Marcus: Well us, firstly. If it resonates with us then we can trust we’re being true to ourselves. We’re fairly accomplished at realising ideas (because it’s what we’ve been doing for a long time) so we are the audience. When you start looking at the audience as ‘the other’ it doesn’t work.

Adam: You need to trust that if it’s going to do something good for you, it’ll do something for other people too. Of course, we go to the shows and see what works and what can be adjusted — at that point you’re in service of your audience. But we treat ourselves as the audience first.

Something I love is that the show is connected with our nephew's mates in their late teens chatting about it on WhatsApp, and people in their sixties at Glastonbury as well. I like to take all those people on a psychedelic, hallucinogenic experience. I’m sure it might be enhanced by whatever drugs people choose to take, but I’d rather the show take them there on its own. I’ve been straight for 12-years now and I used to take a lot of drugs. But I like being transported into another world by a show, and I’d like to think our show and the music does that without needing anything else.

Marcus: Having been through that early rave culture, there are foundational things you remember as quite overwhelming. Going back to your first question, those days are massive influences and it’s this playtime of using incredible gear to create some very strong visual sensations. Some of it is physiological programming — the colours, the strobe, the intensity of light — that’s where the science comes in. There are definitely some visual things you can do which have a strong effect on the brain.

The Chemical Brothers will hit Brisbane’s Riverstage on Thursday 31 October, before heading to The Dome, Sydney Showground on Saturday 2 November and Melbourne Arena on Tuesday 5 November. Tickets here.