David Rudnick: Ideologies

David Rudnick is a UK-born, American-raised, self-taught graphic designer. With a degree in art history and philosophy from Yale University (BA 2009; MFA 2016), his practice is primarily concerned with de-codifying the digitally fragmented environments we operate within; emphasising cultural utility over aesthetic value.

What does it mean to be a graphic designer at this current point in time?

We’re in a moment where what a graphic designer is (or was) and what graphic design constitutes is quite radically shifting, due to not only changes within the profession but within the technological and social paradigm we find ourselves in.

If we’re not there already, we’re rapidly approaching a point where every participant in mainstream social communication is a visual ideator; someone who is participating in the graphic production of communicating their identity through either a curated choice of images, in how one decorates their social media profile, or even whether you choose to create or share memes in your Instagram or Snapchat stories. Most people now are participating in some hybrid communication that, to some extent, involves the traditional skills and choices that would have previously been the preserve of an educated visual class. Font choices, how certain visual decisions represent tone of voice and identity, representation — these skills are now being seen as normative essentials in the participation of every day life.

These were once presented or considered as fringe concerns or negative considerations of the elite; ‘high decisions’ that would take place above people’s heads. I think those illusions are falling by the wayside, while simultaneously the professional class is having to reconcile that the speed and breadth of which decisions take place on a daily basis have outflanked any centralised attempt to control or coordinate them. The number of young people who are aware of (and interested in) how the basic skills of visual communication operate, and understand the way it’s important in their life, is a really startling change. The concern or interest in how branding and identity works makes it almost impossible to participate in contemporary day-to-day society without having some form of relationship with those ideas. Whether it’s one that is codified by a formal education or approached in a very informal manner.

The idea of being excited about processes that can think in ways we fundamentally can't leads to communications which can never be fundamentally understood.

David Rudnick

What has that meant for the consistencies and evolution of your own practice?

Unquestionably there are elements that are not unchanging; particular elements which are destined to be considered ‘consistent’. There are certain themes in how I document and articulate my visual methodology within my own personal space that are consistent.

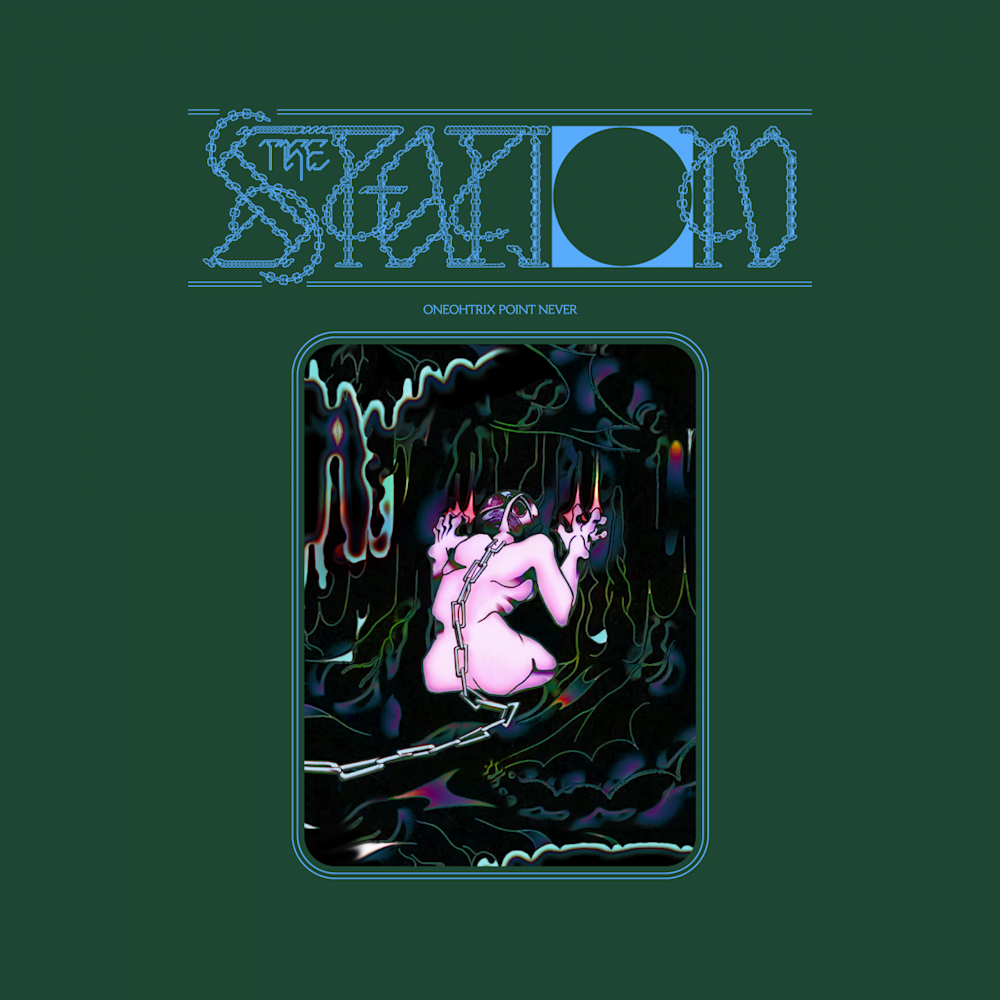

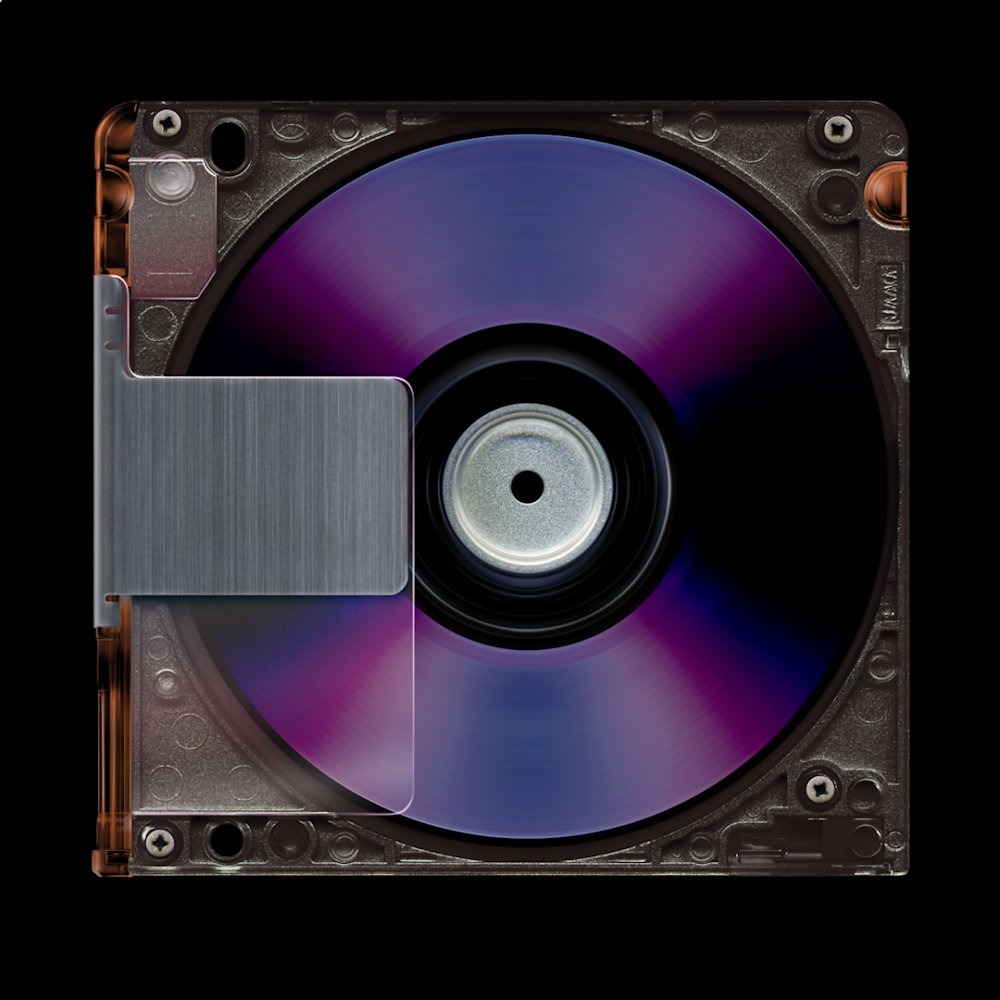

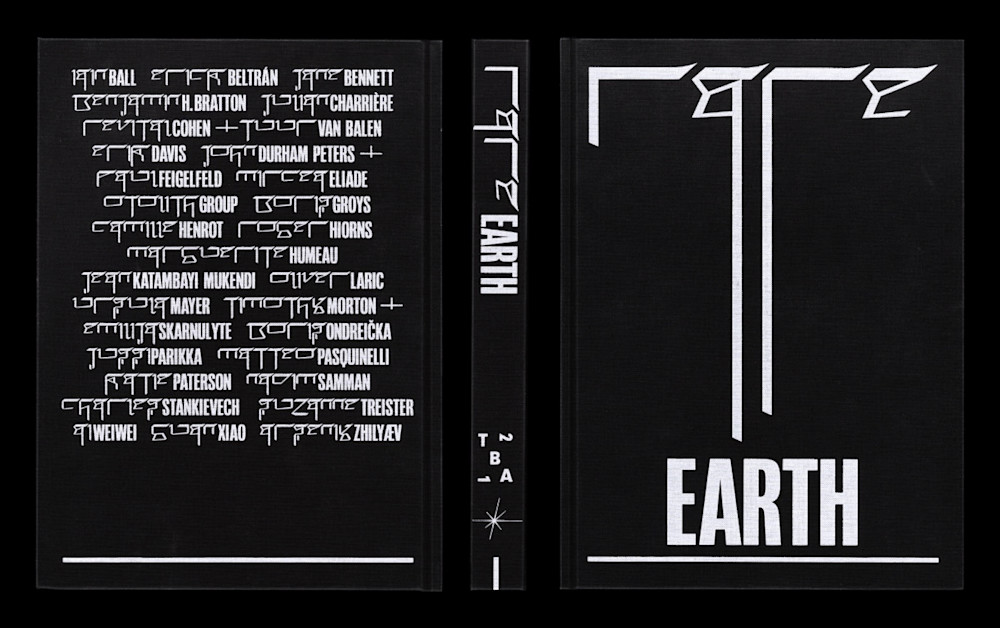

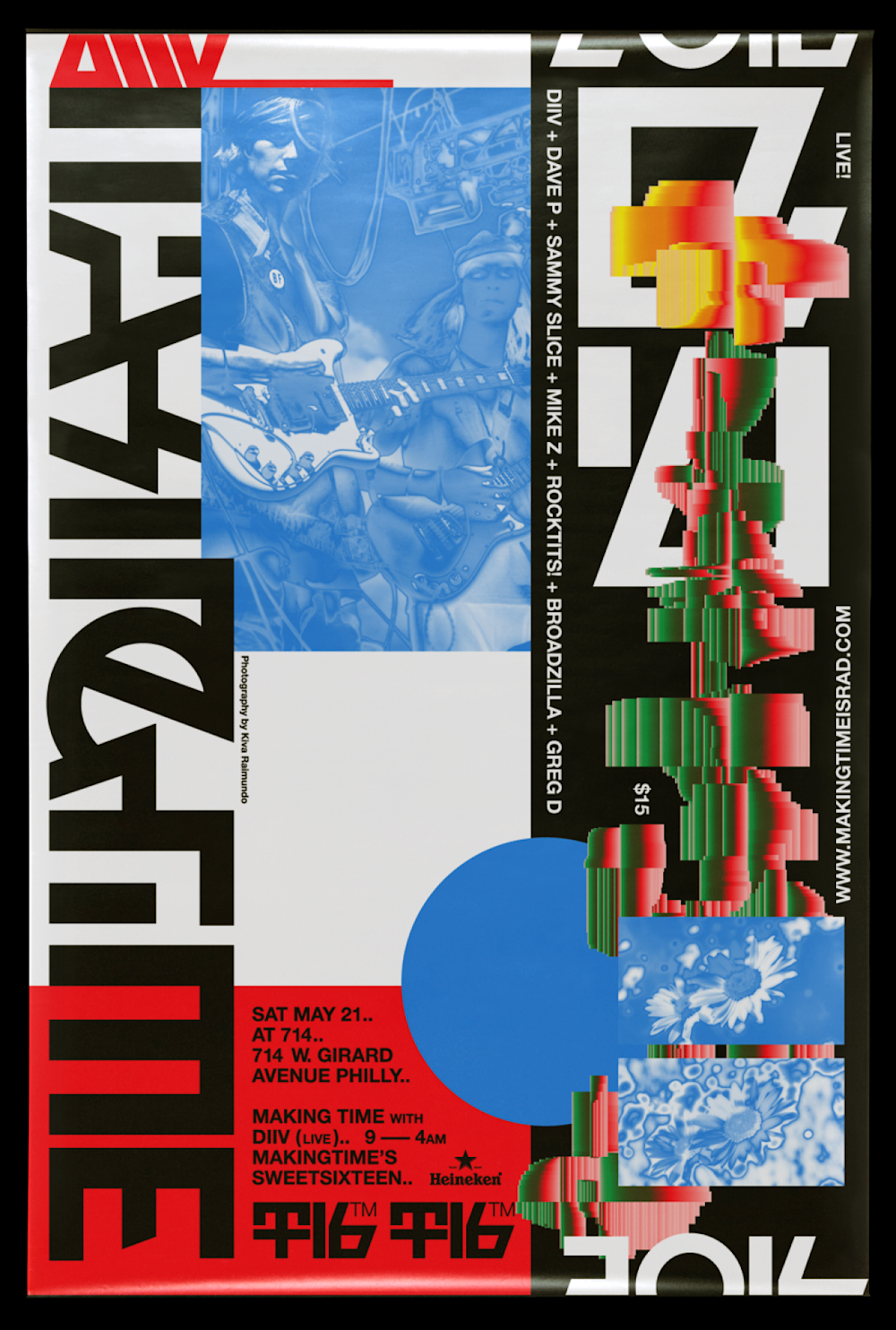

The way the designer documents work as a product of their own process, how the client documents the work, and how the client presents the work must change. I have spoken previously about the concept of Work One and Work Two, where there is a fracturing individual environment wherein every graphic brief generates two works: Work One is the work executed to reach the audience in the context of the client. For example, if I am making an album cover, Work One is the digital artwork that appears on Spotify or the physical record that can be purchased and lives in the life of the audience. It’s very important, essential even, that designers are cognizant they do not need to use Work One (the space that should be an encounter between the work and the audience) to assert their ego as some signature. Defining one’s own practice can be fulfilled by Work Two, which is the way you document the work in the context of it being produced by your practice. There isn’t traditionally a discussion of the difference between these, but I think they’re enormous and in the internet age it’s something which is a new fundamental of design.

Every piece of design for a new client is a totally new vocabulary; a set of ideas they bring to the table, a different audience (who have their own expectations and graphic ideas to activate them), and different levels of visual understanding I need to be mindful of. I would hope when you look at Work One, it’s constantly changing. Consistencies in my presentation as Work Two may mislead people to think I’m trying to create some sort of unified aesthetic and apply it across different projects. When you see my work in the world independently of how I document it, the presence of the designer is far less than when I’m trying to present it as a sequence of ideas I’ve developed in my own practice. I deliberately created a documentation method on my tumblr, where I present my work in sequence one at a time. The goal of that was to show how ideas develop in my practice across multiple bodies of work, or you will see me return to ideas I had previously explored that I think are relevant elsewhere.

I’ve also talked informally to other designers about the concept of ‘the long poem’ where you can view your body of work as an opportunity to explore ideas that may take more time to fully develop than any one client can afford you. It may take 15 years to work out an attitude towards certain fundamentals of the grid or visual composition or historical attitudes to typography, where you need some way of organising those explorations to draw value from them. Part of the role of my tumblr was so I could help organise, for me and observers of my practice, longer term aspirations and ideas. They should never come at the expense of delivering something meaningful for the audience of the work. I don’t want it to feel like it’s another episode of my ‘performance’ of graphic design. My ego should never be present in the Work One that the audience encounters. If so, I’ve failed.

In that regard, can you talk about the long-term client relationships you’ve forged and the ideal structure of any interdependence?

I’m really grateful that it has shown me just how phenomenally varied and special individual creative practices are. They are a reflection of not just individual methodologies but attitudes, experiences, backgrounds, childhoods and environments — things I feel incredibly privileged to listen to and pick up on throughout time. I want to build tools that reflect those ideas and communicate them to their audience rather than having them give me a platform to do ‘me’ on top of their work.

What can be the most rewarding (or disappointing) experience is when those relationships abide over time; seeing someone whose practice you admire grow and change over time and having to learn and change as a result. Whenever I’m approached by a client one of the things I always try and ask is ‘what is the longest-term value we can possibly build out of the work we do together?’. It’s amazing working with musicians or artists because they’re probably going to continue doing that for a long period of time, but it’s equally important to ask that of a more conventional client where what we’re trying to do is deliver meaningful value for the audience. Firstly, we’re not trying to make disposable design and secondly, we’re not trying to give the impression of it being flippant or without longer term meaning or value. Part of growing and learning for me is (having had some incredibly rewarding experiences with individual creatives) how I could try and build relationships with social organisations or conventional companies where we can commit to long-term goals that are of lasting value.

I talked a little at the beginning of my career (and I still feel it’s important) that we don’t have a very good language within design for assessing metrics of recurrence. It’s why I was done with social media early in my career and developed strategies in my practice which were antagonistic or dissentive to what I saw was an environment radically changing design. I believe that would have been more widespread had we placed additional value on the idea that the things you see 10,000 times are far more important and intrinsic to understanding visual culture than something you see only once. There is a tendency, particularly in advertising, of championing graphic spectacle; a fireworks display you see once. What is far more nefarious is your electricity bill or the visual makeup of the social network in which you spend eight hours a day — this is where graphic ideas start to normalise and shape the identities and thoughts of the audience and user.

That's why I started doing magazine design in college. What I loved about them growing up was that in the architecture of my mind, just prior to the internet, it was a place you could return to every month. They had a voice that felt consistent and a graphic attitude where certain things occurred within the magazine that you wouldn't expect to occur anywhere else and you would start to look forward to that experience again the next month. That sense that we are creating both environments and then the social, political and visual culture of those environments become the social, political and visual culture of their audiences is the place from which I approach graphic design. I want to be really clear part of the goal of my practice has always been to better understand how we can create meaningful value for the people who have to view those environments, and for them to become positive places within their lives.

I’ve spent a long time avoiding opportunities to work with corporate clients or brands or networks because I’m still trying to find ways I can put on the table strategies we feel can have long term value. I’m really not interested in creating fireworks for the network, I’d rather help the network become a better environment for its audience.

I don't think the sensitivity of learning to challenge your client is possible when you are punished for challenging your teacher.

David Rudnick

How were these ideologies dictated by the nature of your self-taught education, and what do you believe is missing from present-day design education?

I approach design from a position of distrust and unease. I don’t think I’m a very good student in the conventional sense. If you tell me something is done this way, and I see results in the design industry that look like a pile of shit, I am disinclined to learn to do it the way it’s ‘supposed to be done’ considering I don’t agree with the result. There are an enormous number of young people today who don’t want to end up looking like anything within the design industry as it currently stands. This creates a paradox from an educational perspective because you’re asking people to buy in (often at extreme personal expense) to a certain economic model of renumeration that doesn’t feel like an attractive proposition.

I do think the models of design education as they stand need to change fundamentally. My personal feeling is that paid design education on behalf of the student can not and should not be the norm, or encouraged at all. Publicly available educational resources (freely distributed online) coupled with paid placement (within active studios that have a commitment and incentive to training their staff) is a model that needs to propagate.

When I gave my lecture at The Strelka Institute, I talked about how the Netflix series Chef’s Table had been hugely influential to me. I don’t want to be seen in any way as holding up fine dining as this paragon of superb working practice but it was very clear from these vignettes of chefs (from many different walks of life) talking about how they got their start, that it was practical experience; not just within the industry but from seeking out other practitioners or environments where there was a highly demanding focus on skill. There, they started to assemble a basic vocabulary and palette of understanding and abilities they could apply to their own practice. I do not think the demands of commercial design nor the responsibilities of delivering for an audience can be satisfied fully through the use of practical tutorials in an academic setting. I don’t think the sensitivity of learning to challenge your client is possible when you are punished for challenging your teacher.

It works both ways too. If a design student is fucking about doing work just to be as aesthetically attractive as possible with no actual practical demand (for example, those designers who do a poster a day on Instagram or something), that’s abandoning an important responsibility.

I view myself as someone who grew up in an itinerant way. I was incredibly privileged and didn’t have a lot of responsibility in my life and what I’m most grateful for is that my practice gives me a reason every day to consider my responsibility to other people and deliver in that fashion. I don’t think the current graphic design system in any way addresses this notion of responsibility; I think it addresses liability and it creates transactional relationships where agency can be bought and sold. Similarly, the expectation of the current education model is that design skills are a commodity which can be purchased by a student, which I reject completely. The learning of design skills involves labour, commitment and responsibility on behalf of the student which should be compensated. Ideally we should aim for a situation where all parties — the students, the mentors and the audience — can receive at least some output where every input is valued and respected.

Can you develop that exclusively on your own accord?

You can, but no one develops skills in a vacuum. Everyone has a unique biography, family history, cultural history and social and political background — those are intrinsic, there are no designers who don’t have that. Therefore there is groundwork for a voice, a set of skills or way of framing those skills that will be unique to you. I’m not saying it’s every man for themselves nor am I suggesting people go out and become this self-sufficient individual node, but I think designers should be aware of their practice on a daily basis. They should be sensitive to the way their daily environment is helping them grow or holding them back. If you’re operating outside of education one of the most important things is to find supportive communities: the other designers or clients working towards certain goals whom you can have protection from the precocity of what it means to not work in a structured environment — for example, without a regular pay check.

I can’t stress enough that in my life I would not have got through without the support, patience and understanding of friends. There were times in the first five or six years of my practice which were enormously economically difficult. I was very obstinate in not wanting to take work I felt was socially or personally against my values, and that meant there were times when I was broke. The idea of me advocating everyone goes it alone is awful because I’d be callously putting a lot of people at tremendous risk and harm. I have nothing against and have tremendous respect for people who are trying to build their skills in an environment they determine, and I’d encourage them to remain in contact with other people to learn more about the variety of situations in their space and to never consider themselves distinct or superior. Ultimately it just makes you a worse designer; it will diminish your responsibility to understand what an audience wants or to feel you should be learning about other practices, because that’s what puts opportunities on the table. Communication requires you to have a reasonable understanding of what the other person is saying or needs to hear.

Under the assumption that design is largely dictated by technology, do you think there is a positive impact technology like AI can have in creative fields?

I’d rather it didn’t exist. There’s a privilege to the belief we could get some graphic design while losing the ability to communicate publicly and be trusted as the basis of democracy, or that the more vulnerable in our society may be literally at risk at death because we’re empowering political actors not to be questioned.

Who gives a shit if you could make some cool graphic design? That’s a farcical abandonment of a sincere interest in the essence of graphic design itself. The technology as spectacle — the idea of graphic design as a way of entertaining without thinking — has been enormously ruinous. This is the black-hat side of design where the tools of working are obscured to the viewer. I passionately believe that the design principles on which a piece of work operates should not be withheld from the viewers understanding. And the idea of being excited about processes that can think in ways we fundamentally can’t leads to communications which can never be fundamentally understood. They can empower, and you can make money off them, but it’s at the expense of the viewer or user. It’s part of a power dynamic: the people able to weld those systems most effectively will be the first to access to them; they will have the most money and the biggest social reach at the expense of the audience. They are empowered actors and they hurt viewers. We need to be far more principled in our conversations with one another; if something empowers actors and hurts viewers, we have to stand up and oppose it. We have to. There is no other moral way of looking at that problem, no possible way of suspending it unless you are willing to defend an idea of design as a tool of manipulation at the expense of the audience.

Follow David Rudnick on Twitter.